More from f*ck i love you

the fily (audio)files audio essays | Spotify | Apple Podcasts

f*ck i loved that the pod | Spotify | Apple Podcasts

Welcome to the Welfare Queen Series

This is Part 2 of a three-part series.

Start at Part 1 ^ if you haven’t already.

Part 3’s out next week — June 23, if all goes well.

[Note: I made a short glossary of terms in the footnotes1. ]

Our Second Act

In Why I’m Not a Welfare Queen: Part 1, I shared the story of my mental health crisis and the ‘gauntlet of indignity’ I navigated trying to access Canada’s so-called social supports.

I showed you how my circumstances—eight months out of work, held whole only by my community—are not unique, but rather collective circumstances, deliberately designed.

Today, Part 2, we answer why it is this way. And who made it so.

This is where the personal becomes political—where Mine meets Yours and Ours.

To do any of that, we first need to meet a woman named Linda, the most infamous scapegoat of the last generation.

The Welfare Queen’s Origin Story

"In Chicago, they found a woman who holds the record,” Ronald Reagan began.

“She used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans' benefits for four nonexistent deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year.”

Reagan, a charismatic former Hollywood star and ex-head of the Screen Actors Guild, who’d successfully shapeshifted from a Democratic New Dealer to a staunch conservative governor of California, was stoking intentional rage toward welfare recipients. He thought that rage would carry him to victory in the 1976 Republican primaries.

He’d narrowly lose that primary to Gerald Ford, but would return to win the presidency in 1980 with George Bush Sr. at his side. Both campaigns centred on aggressive promises to reform social spending. In 1976 he promised to cut $90 Billion from the federal budget and gut welfare — sound familiar?

Reagan would be a two term president (1981 - 1989) and earn the moniker The Great Communicator, using his stage craft to seduce the American public into his story of a better possible future, one where “dependency” was abolished, a near moral sin. His antagonist, his villain, his cautionary tale, the woman with 80 names and 15 phone numbers he repeatedly maligned, was Linda Taylor. He made her a main character on purpose.

The Chicago Tribune crowned Linda The Welfare Queen, but it was Reagan’s repeated exaggerations of her crimes that reduced her to a racially charged caricature of America’s social ills.

Never mind that she was only ever charged with stealing $9000 fraudulently — a paltry sum relative to the $150,000 Reagan relentlessly claimed. He even went so far as to suggest she’d netted $1M from the public purse, an even more egregiously inaccurate number.

Say Welfare Queen today, almost 50 years later, and most will sneer as they conjure an image of a lazy, slovenly, conniving unemployed scammer dependent on government handouts. Canadians will instantly imagine an indigenous person, Americans a black person. This, despite overwhelming evidence, including my own story, showing state-sponsored luxury lifestyles are modern myths at best.

Because if anything in our modern world is state sponsored, it is poverty.

Reagan made sure both were true.

He and his friends — who we’ll meet next — would make sure Welfare Queens were at once vilified and eradicated, for the rest of time.

And they achieved their aims at first with only words. Rhetoric. Stories they implanted into imaginations, taking root deep in our collective psyche.

Linda’s story was one piece of a sophisticated, coordinated TransAtlantic strategy to generate political will for a sweeping, transformative policy agenda still shaping lives across the globe today.

Canada is no exception. It is said our politics lag America’s by only one cycle.

Culture does not know borders.

“Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can use that description, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

— Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Canadian Prime Minister, 1969

Meet Milton, Margaret, and Ronald, Architects of the Enshittocene

When it comes to the rest of this ensemble cast, you next need to meet Milton Friedman (1912 - 2006, RIP), a Nobel laureate and intellectual giant, the (brain)power behind the throne. His thinking shaped basically all of mainstream economic thought from about 1970 until today.

I call Friedman the granddaddy of Neoliberal Economics, though some save that honorific for Hayek. Friedman was obsessed with Homo Economicus, a theoretical model of “fundamental human nature”. Some real first principles shit. All of his work assumed humans are perfectly rational, self-interested actors constantly seeking to maximize their own utility. And because of this, we must consider Homo Economicus a main character in our plot, too.

Much like Linda, they implanted him* so deeply in your psyche, you think he is you.

(*And yes. I gendered a concept, for all the reasons you’d assume)

Never mind he’s just a set of largely disproven ideas, divorced from actual human nature — nor with consideration for nurture.

It would take 30 years from conception for Friedman’s ideas to slither from the ivory tower to public policy, their trail greased by Ronald Reagan and his lady friend from the UK, Margaret Thatcher. Enamoured with Friedman’s ideas, he’d serve as their chief economic advisor throughout the late 1970s.

Thatcher, the formidable figure known as The Iron Lady — an epithet given to her by a Soviet journalist — served as the UK’s first female Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990. Like Reagan, she was a staunch conservative who believed deeply in individual liberty and free markets, finding intellectual justification for her own radical vision in Friedman’s work.

Their joint project was to liberate Homo Economicus in each and every one of us, a goal that required dismantling the prevailing economic philosophy: the Keynesian consensus.

The Keynesian consensus, named after economist John Maynard Keynes, was the social and economic philosophy that governed all of The West after World War II. It said that government should actively care for citizens — spending, investing, and ensuring no one fell through society’s cracks. Giving as equal-as-possible access to The Good Life was the goal. It gave us the baby boom and arguably one of the greatest rises in collective wealth and wellbeing in modern history.

It had its problems, to be sure. When a series of socioeconomic crises befell many Western nations through the 1970s and early 1980s, Keynesianism was blamed. This instability also gave Friedman and Friends conditions required to restructure the economic order, attempting to remove all impediments to Homo Economicus’ pursuit of life, liberty and prosperity.

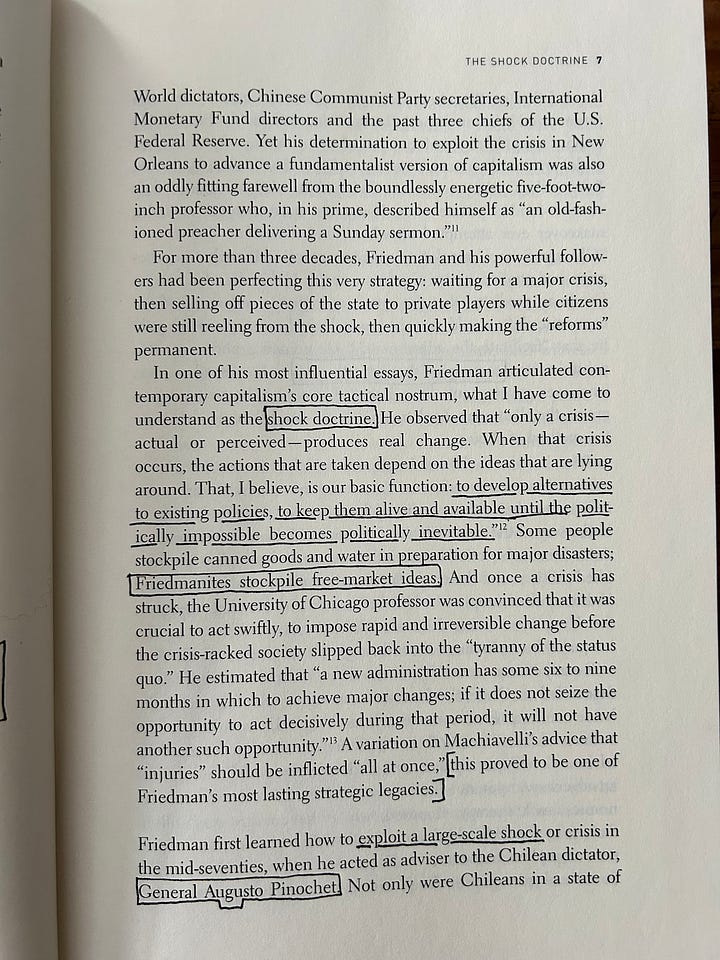

Their tactic of using crisis as a forcing function for transformative change that might not otherwise be accepted is best foreshadowed in Milton’s own words (and p.s., this quote has lived rent-free in my head for twenty years ever since I read it in

’s book, The Shock Doctrine2):“Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.”

Key words:

Crisis.

Change.

Ideas.

Inevitability.

Here we must make a distinction: Change is tinkering around the edges of what already exists.

Transformation is Before and After. An irreversible state change, when something completely new emerges from the ashes of the old.

And if Keynes’ post-war Welfare State was the Before, Friedman’s Neoliberalism is the After.

Indeed, the impossible became the inevitable.

Culture is Your Operating System

But how did they obtain citizen consent to re-write the social contract so thoroughly?

First and foremost, they weaponized culture, specifically and explicitly as part of a strategy to yank Overton’s Window — the sum of publicly acceptable political possibilities — hard, fast, and to the Right.

The trio sought to demonize dependency and make individualism, self-reliance, and free markets the obvious and only solution to social and economic instability.

Thatcher repeatedly insisted, “people accept there’s no real alternative [to these changes].” Her speeches at the time were littered with phrases like common sense and personal responsibility. Her message, like Reagan’s, relentlessly tracked back to Friedman’s theoretical foundation: Maximal freedom to pursue individual economic advantage. Lest we forget: corporations are individuals under the law — and when they said ‘individual freedom,’ they mostly meant corporate freedom.

This is also where we finally get our answer to what disability and poverty have to do with each other, as I pondered aloud in Part 1: disability, like poverty, is a form of dependence. It is a threat to self-reliance and so, must also be demonized.

And while both may have talked incessantly about the economy, Culture, as I previously suggested, was their real battleground. They knew what Terrence McKenna taught us: culture is the operating system.

The Culture Wars are very real and very strategic and this is where — and why — they started3.

And what is culture? A collection of stories based on (shared) values that tell us how to believe and behave.

Economies and governments emerge from culture, not the other way around.

To bend society to their will, Thatcher and Reagan knew they had to first install new shared stories, new beliefs. They had to make you think that you are Homo Economicus, as surely as you are made of matter, and that the only thing standing between you and your God-given right to riches are pesky things like laws, overbearing governments, poor people and lazy scammers like Linda.

They were telling us a new story of the way the world was going to work — and who its villains and victors would be.

But they weren’t writing this story alone.

American presidents can only serve two terms and this was a generational project.

Someone else would need to pick up the baton.

The Original Bromance Quickens The Enshittening

There is perhaps no better explanation of what it means to move Overton’s Window hard fast and to the Right, than the fact Reagan and Thatcher’s radical conservative project was completed by Bill Clinton and Tony Blair throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

And yes, if you’re old enough to remember these guys, you are correct to be confused because Bill Clinton is a Democrat and Tony Blair is Labour, both ‘left of center’ parties.

They were progressives implementing a conservative agenda because the range of political inevitabilities had been so completely colonized by Friedman’s vision. Neither of them could have been elected without serving this project.

The cultural operating system had been reprogrammed.

Clinton, a Democratic President from 1993 - 2001, would, among other things, take their project global. He broke down barriers to international trade with the introduction of NAFTA, ‘ended welfare as we knew it’, and critically, repealed Glass-Steagall, a set of banking regulations that arguably, once removed, set the stage for the 2008 financial crisis4.

These policy changes would lead to staggering shifts such as a 78% decrease in access to Temporary Assistance between 1993 and 2016, despite need for support increasing. Or, as another example, the debt-to-disposable income ratio of American households more than doubling from 60% in 1980 to 133% in 2007. I’ll stop there, but only to respect your attention. Data on these impacts abounds.

So when you hear people talk about “regulatory capture” know that this is basically what they mean. A decades long project to enable corporations — Homo Economicus’ ‘Doing Business As’ persona — to supersede governments.

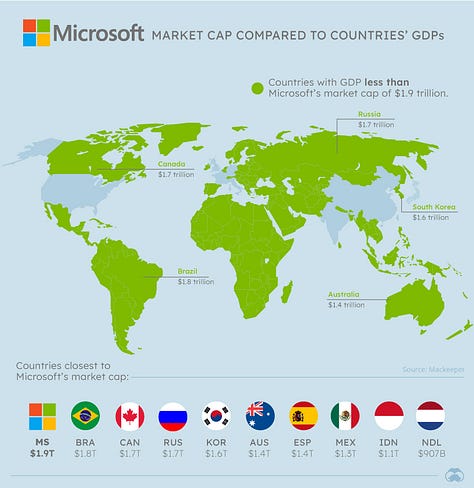

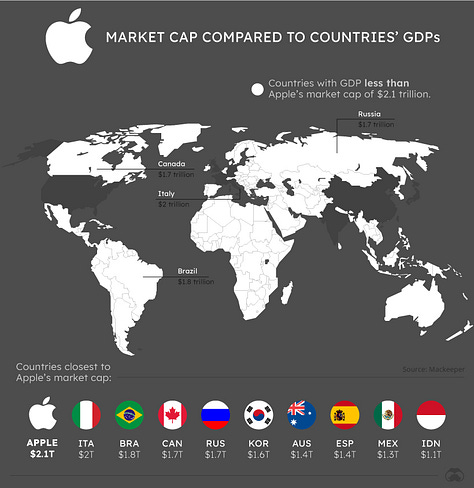

This is also how you get tech companies with valuations greater than the GDP of 96% of all nations, including Canada, their power so absolute no government dare intervene.

And, how you get governments functioning as ‘adversarial insurance companies’ in service of maximizing private wealth at the cost of collective wellbeing.

And all this could only happen because electorates demanded it — and continue to.

Citizens were certainly manipulated into these demands — Reagan was The Great Communicator after all — but once you change a belief system, you change the nature of reality itself.

Humans are funny that way.

We bend reality to our beliefs, even when our beliefs are not necessarily rooted in reality.

This is the real inception shit.

The enshittification shit.

A Short History of The Enshittocene

Here is the point where we go full meta-synthesizer and pull everything into clear focus, attempting to bridge our series together. That is the purpose of a Second Act, after all.

I introduced enshittification in Part 1, a term coined by

to describe the internet’s gradual deterioration as a consequence of profit seeking. Except it didn’t just happen to the internet.That came later.

First, we practiced on our public services. And if enshittification describes the deterioration of those services, then the Enshittocene is the period in which it occurred. And it is not just Homo Economicus’ natural habitat, but his greatest achievement.

Based on what we’ve learned today, I will suggest it began in 1980, the year Reagan was elected and the year the first Millennials were born, an entire generation of main characters we’ll meet in Part 3.

After all, the Chicago School project, as we’ve well covered, ushered in the greatest deterioration of our public services and collective quality of life in modern history. This enshittification wasn't limited to digital platforms, but rather, their rapid destruction mirrored our own; it was the same forces, the same logic, just on an accelerated timeline.

Our obsession with technologically-enabled efficiency during this same period increased our capacity to destroy exponentially: it took Friedman and Friends approximately 40 years to achieve the near total destruction of the commons in pursuit of their theoretical utopia. We managed to destroy the digital commons once known as the internet, in only 10.

This is what happens when maximizing efficiency and hockey stick curves on investor growth returns become the primary cultural pursuit.

We’ve lost the plot of what the point of rapacious maximization to the power of machines is, and destroyed much of what makes life worth living in the process — especially and including the resources to sustain it.

And this playbook for manipulating culture to create inevitabilities that send investor returns to the moon — as

pointed out in their must-read article, The Great Myth — is being used to advance the next “inevitability”, a future where AI replaces humans. That story, that myth as Gil correctly calls it, is very much driven by the wealth and efficiency maximizing logic of our self-interested friend, Homo Economicus. I won’t take us on a side quest into that discourse — yet. It is very much related to the story I am telling though, and will matter when we get to Part 3.And speaking of Part 3, the quickening enshittening gave rise to two critical populations we’ll be pivoting to next: The Precariat, who I introduced in Part 1, and The Millennials, who I just alluded to.

Maybe we could call them Homo Economicus’ bastard offspring, struggling for survival in a post-dignity world.

And let's be brutally clear about what this means for us, for the Mine, Yours and Ours we've been tracing: As we covered in Part 1, when two-thirds of a country’s citizens are living precariously, one unexpected bill, one health crisis away from financial ruin, that is a design choice.

A very real, very painful outcome of a culture war fought and won by a powerful few.

A feature, not a bug.

Prelude to Part 3

One thing Friedman was right about is that crisis produces real change. And make no mistake that crisis — a polypermacrisis, in fact — is upon us. This might be our last chance to avoid accelerating into the shit storm, if only we understand where we’ve arrived.

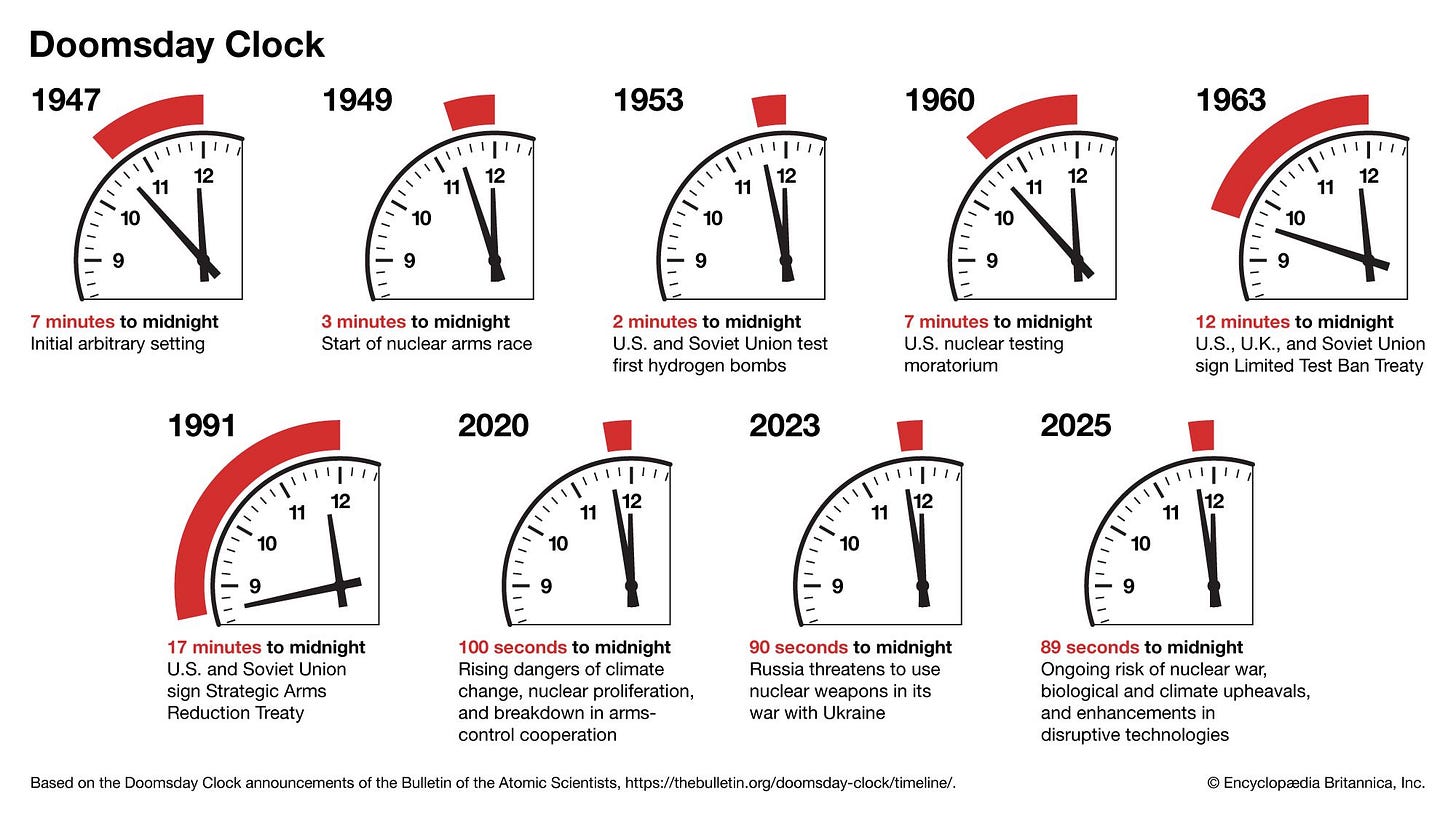

And where we’ve arrived is 89 seconds before midnight on the doomsday clock, just long enough to choose which version of transformation we prefer.

And this moment — these 89 seconds, more precisely — is exactly where Part 3 picks up. We’ll turn our gaze to the aforementioned Millennials, the original digital denizens of the Enshittocene, a generation living worse outcomes than their parents, the precarious progeny of a failed socioeconomic experiment.

We’ll get into how we might de-shittify things, we’ll say buh-bye to TINA, The Iron Lady’s not-so-iron-clad lie that There Is No Alternative to the Great Enshittening, and explore the mannnnnnny excellent ideas that lay about for how we might build a generative future.

So tune in for Part 3 where we’ll wrap up this trilogy by making clear the future that’s already here, just not equally distributed.

And very much requires our agency and active participation to realize.

Footnotes

A Quick Guide to Our Economic Terms

Neoliberalism: An economic and political philosophy that advocates for free markets, deregulation, privatization, and minimal government spending, aiming to maximize individual economic liberty. It opposes government intervention in the economy.

Keynesian Consensus: The dominant post-WWII economic philosophy that emphasized government intervention, spending, and regulation to manage the economy, ensure full employment, and maintain social welfare programs.

Overton's Window: The range of policies considered politically acceptable to the mainstream population at a given time. Shifting the window means changing what ideas are seen as reasonable or even possible.

Stagflation: An economic condition characterized by slow economic growth (stagnation) alongside high inflation and high unemployment, a phenomenon considered unusual and difficult to address under traditional economic theories.

Bretton Woods System: An international monetary system established after WWII that fixed exchange rates to the U.S. dollar, which was in turn pegged to gold. It aimed to stabilize the global economy and facilitate international trade, until its collapse in the early 1970s. This is when fiat currencies arrived on the scene, meaning governments can print their own money, backed only by their reputations, with no relationship to precious resources or tangible goods. Think of fiat currencies like vibe currencies.

In university, I cheekily, but kinda seriously listed Naomi Klein as my religion on Facebook. Mega fangirl. The Shock Doctrine is still on my bookshelf. Here’s a documentary about her ideas. Also highly recommend Capital in the Twenty First Century (trailer below). HMU if you want more recommendations.

The “start” of the culture wars is a debated subject among academics. Some trace it back as far as 1920, but the general consensus is their modern incarnation that is impacting us today started in earnest in the 60s, picking up steam with Reagan et al. in the 1970s.

You must, must, must!, watch The Big Short if you have not already. It might be my favourite movie. It tells this story but way better, tracking the 2008 financial crisis/The Great Recession back the ~1970s. Plus Ryan Gosling and Christian Bale times Margot Robbie. Thank me later.

***

If this piece lit up your brain and heart at the same time, sharing, liking, commenting or subscribing is Creator Speak for “fuck i love you, too”.

And let’s be honest this is still capitalism and this economy is shit (again) so I don’t use paywalls. If you’re in a good position and excited to

make a one-time or monthly contribution,

I’d be super grateful.

I’ll still fucking love you either way.

***